In my previous post on VC ownership when investing in startups, I received numerous questions from entrepreneurs seeking to better understand the expectations of funds when they invest. As such, it’s useful to spend some time unpacking the Power Law.

The Power Law states that in a typical VC portfolio, a small number of companies generate the majority of returns. The industry, as a whole, hinges on the success of a few companies. This contrasts with traditional portfolio strategies, which assume asset returns are normally distributed and produce uniform returns.

In VC, outliers drive returns.

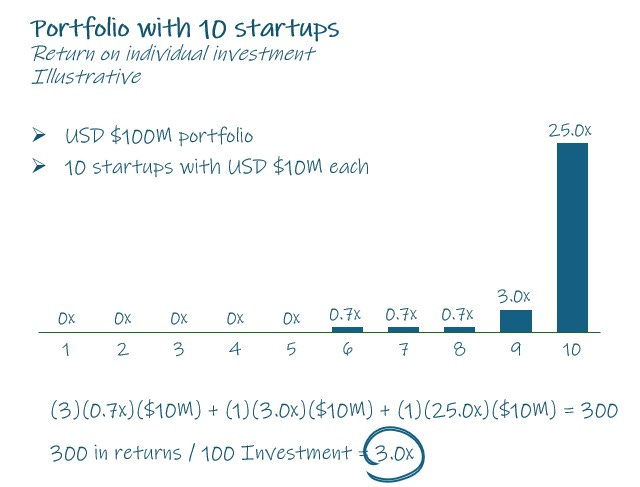

Let’s review a simplified example of the Power Law, which assumes a portfolio where the fund invests the same amount in each startup. In this example, the top investment is responsible for over 80% of the returns in the portfolio, while the top two investments account for over 90% of the returns.

The Power Law is an evolution of the Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule—a statistical regularity stating that 80% of outcomes come from 20% of causes. Adapting the Pareto Principle to VC, less than 20% of investments account for over 90% of a fund’s returns. This dynamic has at least two important implications:

Failed investments don’t matter (that much).

While VCs focus on outliers, some managers emphasize achieving at least a 1x return on each investment. Although this may seem insignificant without a fund maker, it can significantly boost a fund’s overall performance when paired with one.Every investment must have the potential to be a home run.

This explains why VCs are stringent about ownership. Beyond having the right team, a scalable business model, a massive market, and favorable timing, the deal structure must ensure that, if the startup becomes an outlier, it can materially impact the fund’s returns.

As a result, a typical return profile for a VC fund may look something like this.

The 10x Principle

One common question from entrepreneurs related to the Power Law is: What about the 10x principle? Specifically, if a VC invests $1M in my company at a $10M valuation, and my company grows to a $100M valuation, are we good?

The answer is: Not quite.

(Though it’s a step in the right direction.)

As I mentioned in my previous post, if a portfolio company performs well, the VC firm will likely invest in subsequent rounds. For instance, an initial $1M Seed investment may be followed by additional investments across 2-4 subsequent rounds (e.g., Pre-Series A, Series A, Series B). If the VC is managing a ~$100M fund, their total investment in that company might range from $7M to $15M.

For the 10x principle to hold, funds would need a 10x return on their total investment, not just the initial $1M. This means the multiple on the first check might need to be 50x, 100x, or even more. VCs measure both the multiple on the initial investment and the blended multiple across all investments in the company.

Let’s revisit the earlier example: if the company exits for $100M and the VC retains 10% ownership (without further investment), the fund would receive $10M. This represents 10% of the fund size—an excellent return for the entrepreneurs and early employees, possibly a life-changing windfall. However, the VC may still be disappointed, as they missed the opportunity for a Fund Maker.

Summary

Under the Power Law, Fund Makers typically yield multiples well above 10x, even if they only account for a small portion of the total invested capital. The key to understanding VC dynamics lies in recognizing that returns are driven by outliers, making it essential to structure investments for outsized outcomes.